It’s well-known that the seedings prevent number 1 and number 2 from meeting each other until the final. What’s not as well known, because people often neglect non-favorites, is that number 3 and number 4 can also not meet each other in the final.

With Federer and Nadal being so dominant, usually one or the other reaches the final, thus spoiling a 3 vs. 4 match up. For as long as Djokovic and Murray have been 3 and 4, they’ve never met in a Slam final. Indeed, in all of 2009, neither reached a Slam final at all, despite Federer and Nadal only meeting each other once (in the Australian Open in 2009).

Technically, Murray was the fifth seed heading into the Australian Open courtesy of Robin Soderling, who won Brisbane, two weeks before the Open, and thus was able to apply those points to move ahead of Murray. Murray had a bit of luck. He ended up falling in Soderling’s quarter. He can thank Ivan Lendl for that (who did the draw, placing the seeded players). For a while, that didn’t appear to be the best quarter given how well Soderling was playing. Murray was in danger of having to play Soderling, Nadal, and Federer in back-t0-back-to-back matches.

Turns out, he didn’t play any of them. Soderling was upset by the tricky Dolgopolov. Murray needed some tough tennis to get past Dolgopolov. He probably could have gotten by Soderling, perhaps even easier than Dolgopolov.

Then, Ferrer upset Nadal. Murray would probably have been thrilled to play an injured Nadal rather than a healthy Ferrer. This match was mostly in Murray’s favor and became a bit tougher than it should have been.

The last two times Murray played Ferrer, it was decidedly in Murray’s advantage. Murray’s not a great clay court player, and Ferrer has beaten him all meetings on clay.

Its easy, of course, to forget that two players were playing in the semifinals. As much as the announcers were saying that Ferrer was dangerous (he is), the fact is, most just thought of Ferrer as the guy that was in the way of Murray reaching the final.

Everyone said Ferrer had been undefeated in 2011. Of course, prior to the Australian Open, that could be said of many players. It could be said of Wawrinka, who won Chennai. It could be said of Federer, who won Doha. It could be said of Simon, who won Sydney. It could be said of both Djokovic and Murray who played an exhibition (admittedly, winning all their singles matches).

The fact of the matter is that Ferrer had a great 2010. He was in the top ten for a reason. His run began early in the year just after the Australian Open. The clay season falls in 3 parts. The period of time between the Australian Open and Indian Wells which is a Latin American swing in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. Ferrer reached two finals with Ferrero, and split one with him. Then, Ferrer did well in the major clay season after Miami and leading to the French.

He unexpectedly lost to Jurgen Melzer. Who knew a 29 year old that had never gotten past the fourth round would have his best year too? There was the clay season after the French Open.

Ferrer ended the year well getting to the finals of Beijing where he was crushed by Djokovic and winning Valencia, which is his own tournament (I think, with Ferrero). With his win in Auckland, no one could deny that Ferrer had become a good hard court player. Indeed, his only other Slam semi was at the US Open, not the French.

Despite the kinds of problems Ferrer poses to many players: his speed, his tenacity, the fact of the matter is that Ferrer relies more on placing the ball and playing aggressive tennis within those parameters. Ferrer isn’t like Soderling that can bludgeon the ball, but he is a good backboard, and can return lots of balls hit with pace. But without a huge power shot, he can’t take over points easily.

Murray was willing, at times, to go toe to toe with Ferrer, playing his style. He would get into long drawn-out rallies. This is impressive given Murray’s flatter style and his general timidity when it comes to pulling the trigger. Murray likes to keep the balls with huge margins of safety. The times he goes for big shots, he can often spray it a bit wide to very wide. Unlike Federer, who is used to hitting at the lines, Murray has to convince himself to do it.

As the other pros have gotten used to his game, and as his playing style has not given him the tools to reliably beat the best, Murray has been adding shots to his repertoire over the years. Against Nadal, Murray added a short crosscourt forehand aimed at the corner of the service box. This is not a sharp angle winner shot a la Davydenko. This was supposed to get the ball into Nadal’s backhand so he wouldn’t run around it (the angle being too sharp).

In the last year, Murray added a hard hit crosscourt forehand deep, which he uses when he gets drawn wide to his forehand. Lately, he’s been working on his down-the-line shots on forehand and backhand. Perhaps the biggest difference between the way Murray and Djokovic play, other than the spinnier style of Djokovic, is Djokovic’s preference to hit down-the-line on the backhand. Murray is trying to learn this shot and hit it more in match situations.

It’s not that, of course, that a pro of Murray’s caliber can’t hit a down-the-line backhand, but it is a conviction shot. It’s always been considered low percentage, so you have to believe, at the biggest moments, that you can make this shot. Murray is a strongly crosscourt player. He prefers hitting crosscourt where he’s far more confident.

One reason Ferrer had good success playing Murray last summer was Murray’s strong preference to hit crosscourt (or feat of hitting down-the-line). Ferrer would maneuver to the ad side, and pummel Murray’s backhand, knowing almost all shots would come back crosscourt. He would then use his steadiness to get an error from Murray. Murray couldn’t find the nerve to go for a big down-the-line shot.

Murray’s been trying to develop the running down-the-line shot. This is partly a response to Nadal who can drive Murray to his right. Most players, in that situation, hit a powerful shot to Nadal’s backhand, except Nadal is often camped so far to his right that he takes it with a forehand, and can drive it inside-in up the line. The down-the-line shot keeps a player like Nadal honest. If he goes for that huge inside-out forehand, a player can respond down the line.

Indeed, this used to be a shot of choice for Lendl. If you forced him to move to his right, Lendl would try to crack a down-the-line winner. Sampras showed an alternate response. When Agassi hit an aggressive crosscourt forehand, Sampras would hit a reverse forehand, creating a huge angle and often hitting a winner. It was the one shot that Agassi could never handle. If Sampras didn’t have that shot, Agassi wins a lot more matches against Sampras.

Murray had chances to close this match out quicker. Although he was a set point down in set 2, he also got a break up, but was broken when he tried to serve for the set. Fortunately, he had a very lopsided tiebreak. Murray adjusted his tactics to play Ferrer in the second set. Normally known for playing many meters behind the baseline, he moved closer to the baseline trying to take balls on the rise and cut time off from his opponent, as well as make forays to the net. This is another facet of the Murray game, added to deal with opponents who would maneuver him around from back there.

One year, Davydenko beat Murray in Shanghai in the year-end championships during a semifinal match because Dayvdenko plays at the baseline while Murray stood way back. Murray has responded to his critics by adding these wrinkles to his game to make him more well-rounded.

Murray took the third set easily, and lead 2-0 in the fourth set, but got broken back immediately. The two held serve until another tiebreak where Murray again took command early and won it.

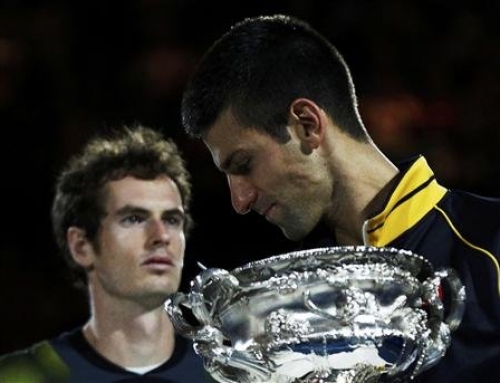

OK, so now we have the final no one (except me in a pool where I was just being contrary) predicted.

Djokovic has, on paper, had the harder route to the final. He played, in succession, Troicki, Almagro, Berdych, and Federer. Troicki was a walkover. Almagro and Berdych he crushed, and Federer he played a great match to keep Roger at bay.

Murray played Garcia-Lopez, Melzer (both lopsided wins), Dolgopolov and Ferrer (both four set matches).

Djokovic, however, has a different challenge in playing Murray. Both Federer and Berdych play a fairly aggressive style. Djokovic neutralized Berdych by playing lots of shots to one corner forcing Berdych to reverse directions again and again, which is a huge challenge for a big guy like Berdych. Against Federer, Djokovic used his solid return game to force Federer to play out each point.

Federer relies rather heavily on his serve to give him a few free points. When he’s on, he gets 2-3 free points a game where he doesn’t have to work. This is huge for Federer, because Federer isn’t steady enough to play every point. With a precise serve, Federer can take more chances on groundstrokes and he looks great when he does that. Imagine if players could return the Sampras serve. Instead of being the huge Slam champ he is, he might have been a guy like Edberg who won his share of Slams, but otherwise, not among the very best.

Murray’s weakness, his low first-serve percentage combined with a less than aggressive second serve, might be a weird blessing in disguise. Like Nadal, Murray doesn’t need his serve to win games. He has been getting a few free points off it, and it’s still crucial for him to win, but he manages to win games despite a low first-serve percentage. Since Murray isn’t a bang-bang player like Federer or Berdych, he poses interesting challenges to Djokovic. Murray is willing to stretch out rallies with neutral shots.

Djokovic is not nearly as opportunistic as Nadal when given a neutral ball. Nadal can take a plain old ball up the middle and then whip it to one side or the other for a winner. Djokovic is less likely to do this, and instead, maneuver the ball around to get an opening.

A key to both their games is the return of serve. How much can each player pressure the other? Both players have shown a mental tenacity. Murray’s game is prone to streakiness and because he’s not nearly the aggressive player that Djokovic is, he can sometimes find himself struggling. In the Dolgopolov and Ferrer match, he had to deal with two kinds of players that can give Murray trouble. Dolgopolov is a high-risk player that can hit hard crosscourt or down the line at the drop of a hat, from court positions that seem unwise. But Murray weathered that storm and weathered the Ferrer storm too. In the past, Murray might have buckled under the pressure he was feeling. Yet, somehow, he got past that.

So I think Murray has a reasonable shot at the win because he doesn’t play like Federer or Berdych. The key will be how Murray recovers. If he can recover, I think this has the makings of a very exciting match.

Apparently, Djokovic has started with the mind games saying he was glad that he didn’t have the pressure of the British media on him. To be fair, Murray has dealt with this pressure forever, including Roger’s jibe at him last year. Murray is learning how to deal with this and getting to playing his game. I think if the Ferrer match didn’t wear him out too much, it will be very good, because he hit a lot of balls and ran around a lot. Courier noted the weather is likely to be quite a bit warmer for the finals. Djokovic has yet to be pressured in heat, and although the match is played at night, it is a possible wildcard. Djokovic, for his part, will want the match to be quick. Although Murray doesn’t exactly want to play a lot of sets either, if he can make Djokovic run too, it might prove interesting.

![[Aussie Open Final] Can Andy Murray beat Novak Djokovic?](https://www.essentialtennis.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/20130126andy-500x383.jpg)

![[Day 13, Aussie Open] Bryan brothers win 13th Slam with Aussie doubles title, Kyrgios wins boys title](https://www.essentialtennis.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/20130125bryan-500x383.jpg)